Warning: Graphic content, readers’ discretion advised. This article contains a recollection of crime and can be triggering to some, readers’ discretion advised.

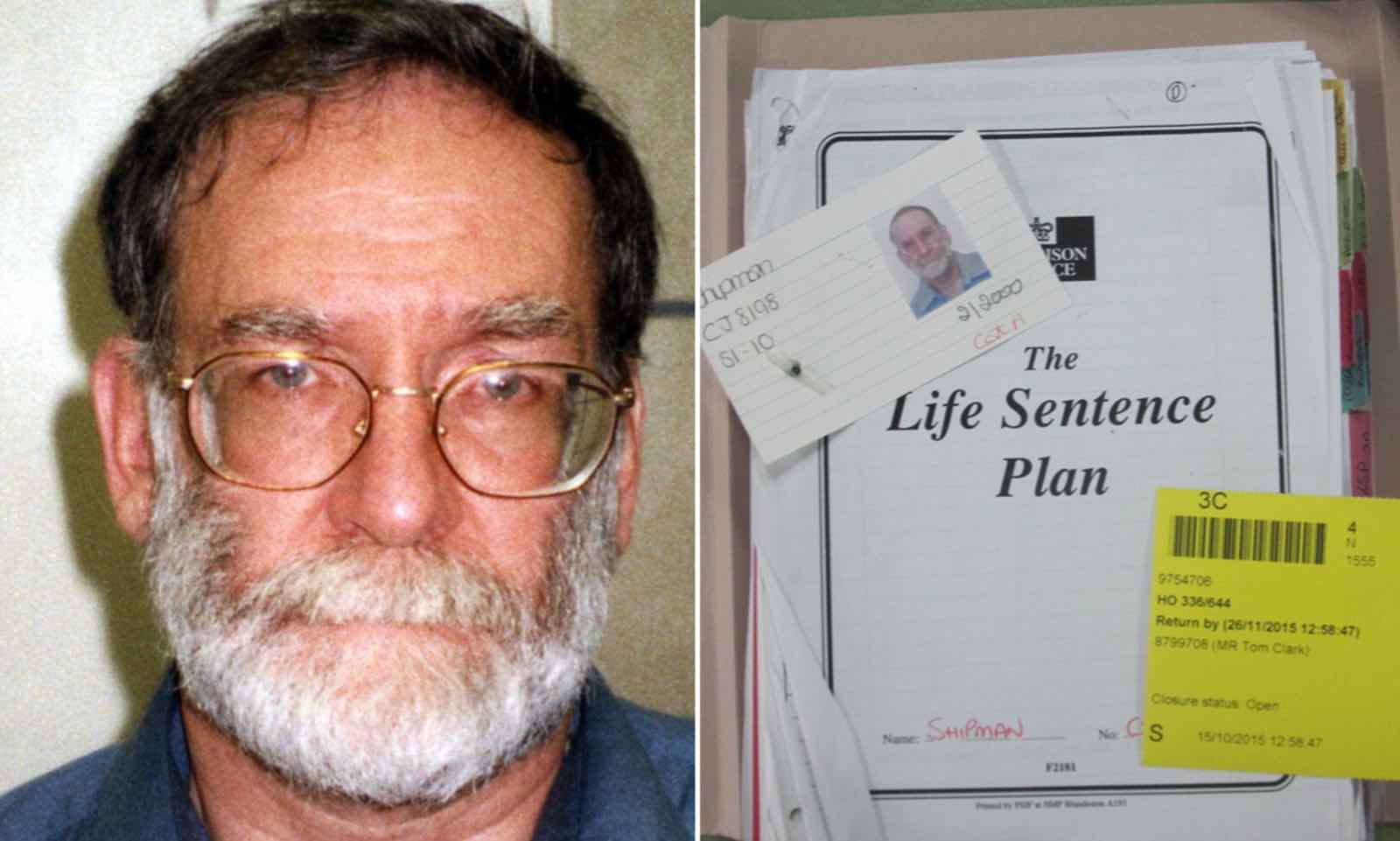

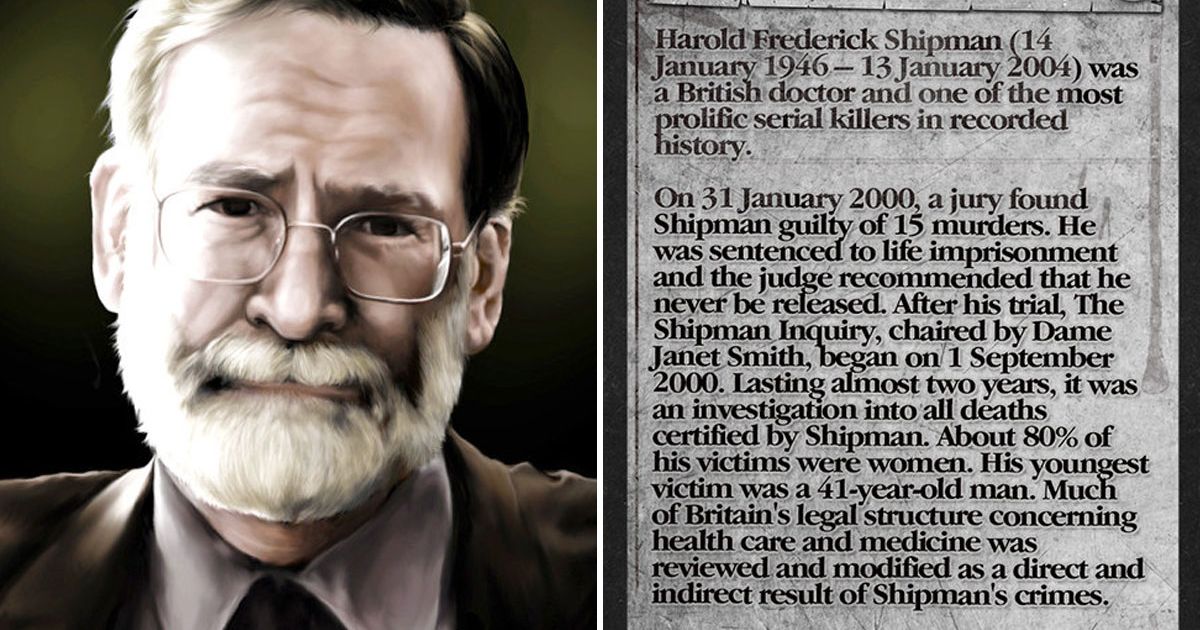

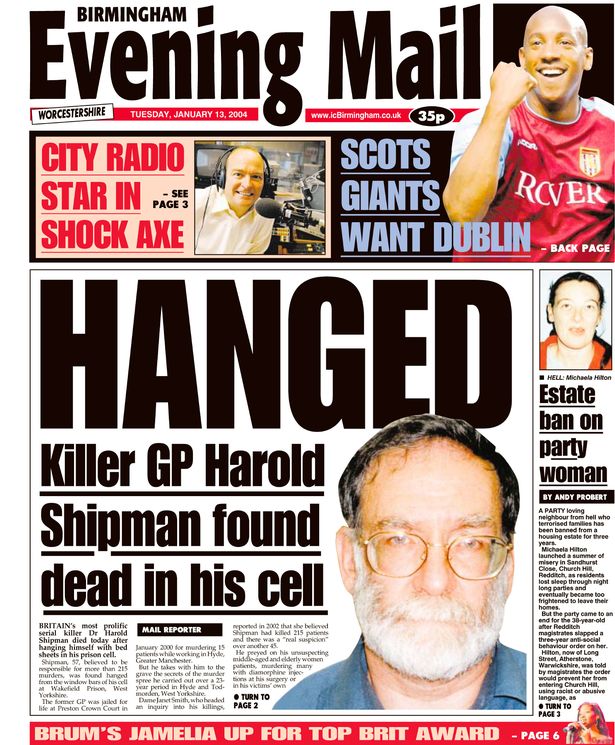

Harold Frederick Shipman (14 January 1946 – 13 January 2004), known to acquaintances as Fred Shipman, was an English general practitioner and serial killer. He is considered to be one of the most prolific serial killers in modern history, with an estimated 250 victims. On 31 January 2000, Shipman was found guilty of murdering 15 patients under his care. He was sentenced to life imprisonment with a whole life order. Shipman died by suicide by hanging himself in his cell at HM Prison Wakefield, West Yorkshire, on 13 January 2004, aged 57.

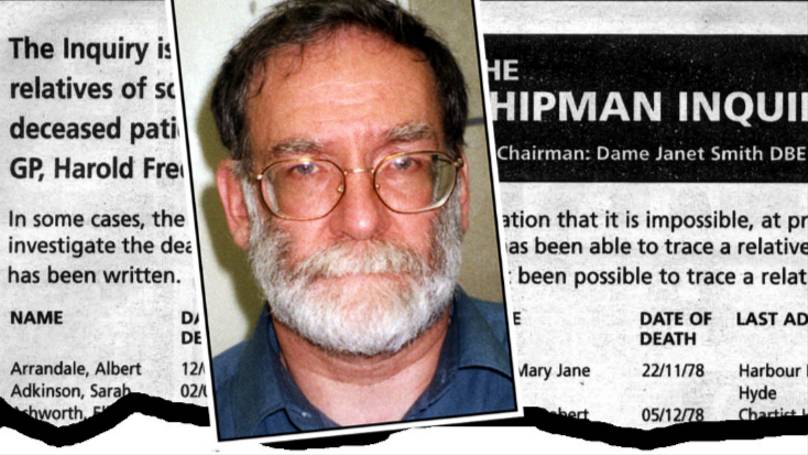

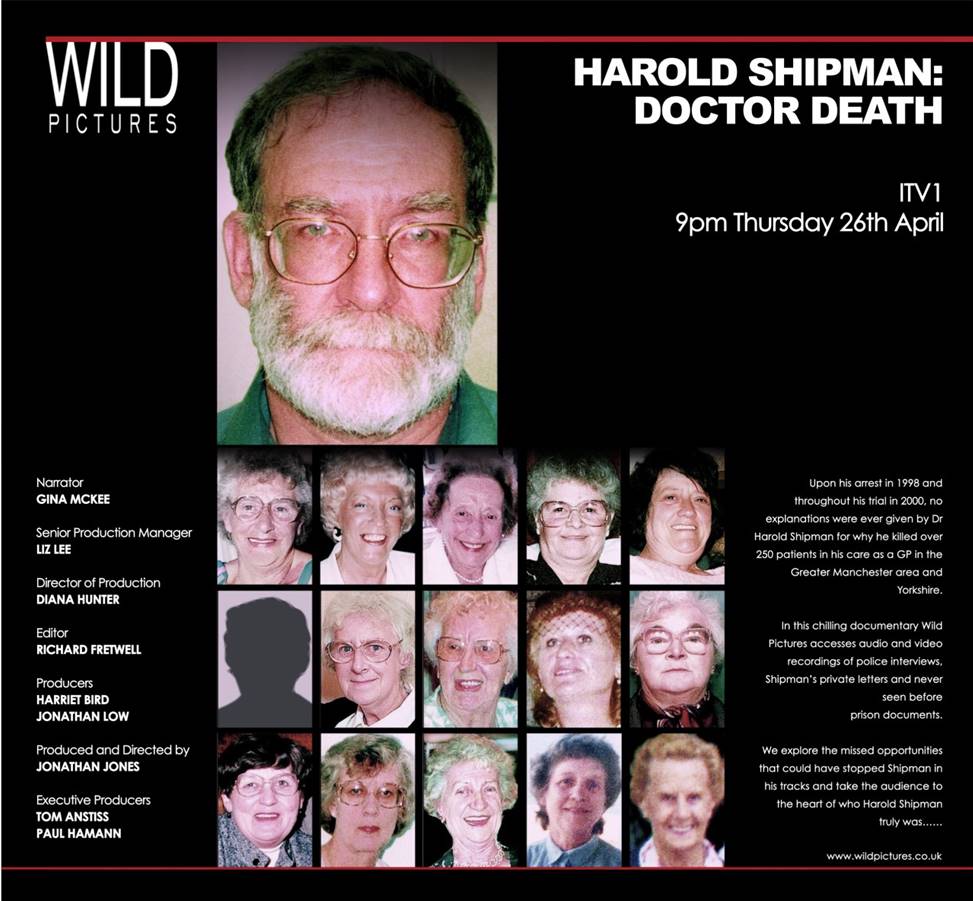

The Shipman Inquiry, a two-year-long investigation of all deaths certified by Shipman, chaired by Dame Janet Smith, examined Shipman’s crimes. It revealed Shipman targeted vulnerable elderly people who trusted him as he was their doctor. He killed his victims either by a fatal dose of drugs or prescribing them an abnormal amount.

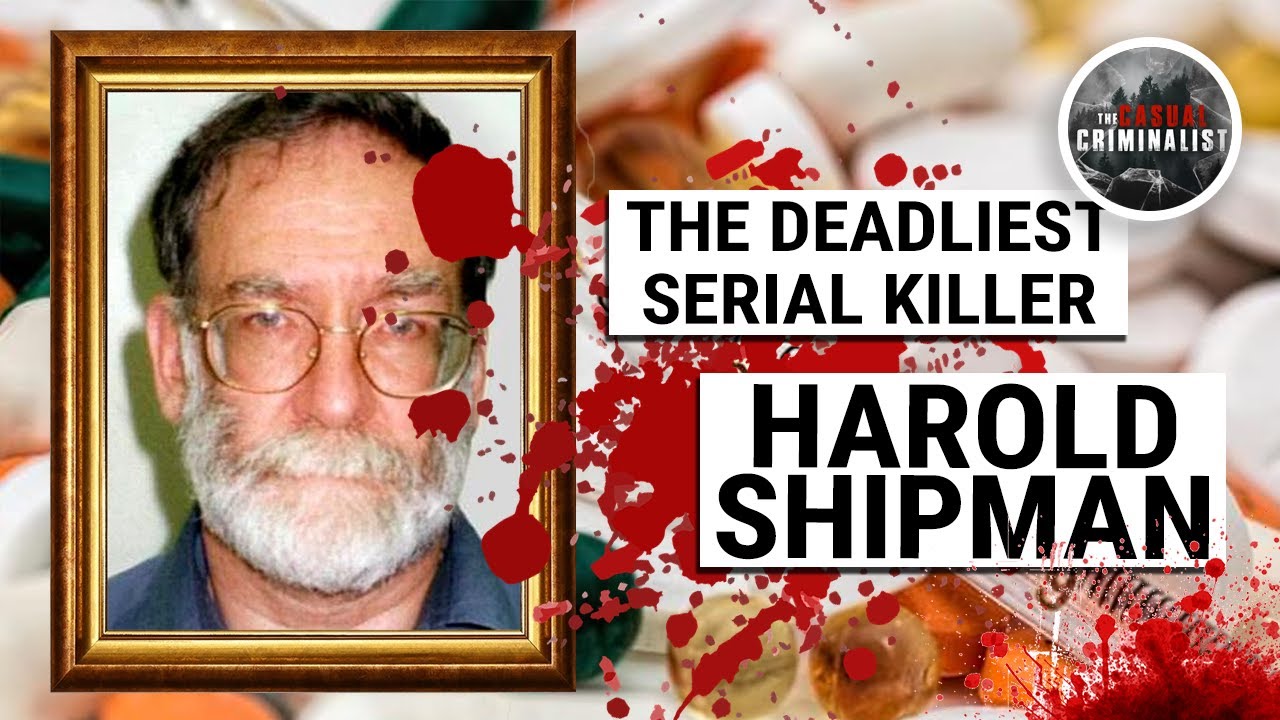

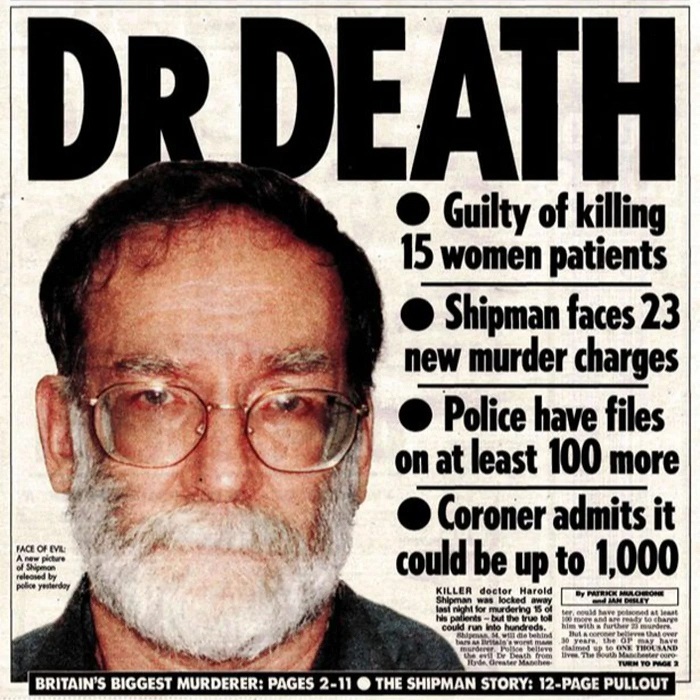

Shipman, who was nicknamed “Dr Death” and “The Angel of Death”, is the only British doctor to date to have been convicted of murdering his patients, although other doctors have been acquitted of similar crimes or convicted of lesser charges.

Shipman was born on 14 January 1946 on the Bestwood Estate, a council estate,in Nottingham, the second of the three children of Harold Frederick Shipman (12 May 1914 – 5 January 1985), a lorry driver, and Vera Brittan (23 December 1919 – 21 June 1963). His working-class parents were devout Methodists. When growing up, Shipman was an accomplished rugby player in youth leagues.

Shipman passed his eleven-plus in 1957, moving to High Pavement Grammar School, Nottingham, which he left in 1964. He excelled as a distance runner, and in his final year at school served as vice-captain of the athletics team. Shipman was particularly close to his mother, who died of lung cancer when he was aged seventeen. Her death came in a manner similar to what later became Shipman’s own modus operandi: in the later stages of her disease, she had morphine administered at home by a doctor. Shipman witnessed his mother’s pain subside, despite her terminal condition, until her death on 21 June 1963. On 5 November 1966, he married Primrose May Oxtoby; the couple had four children.

Shipman studied medicine at Leeds School of Medicine, University of Leeds, graduating in 1970.

Shipman began working at Pontefract General Infirmary in Pontefract, West Riding of Yorkshire, and in 1974 took his first position as a general practitioner (GP) at the Abraham Ormerod Medical Centre in Todmorden. The following year, Shipman was caught forging prescriptions of pethidine for his own use. He was fined £600 and briefly attended a drug rehabilitation clinic in York. He worked as a GP at Donneybrook Medical Centre in Hyde, Greater Manchester, in 1977.

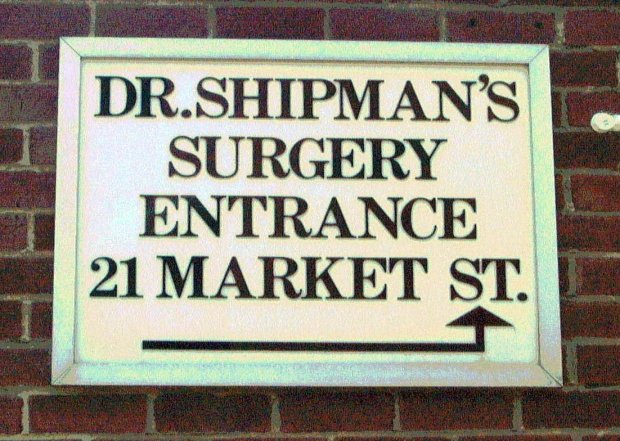

Shipman continued working as a GP in Hyde throughout the 1980s and established his own surgery at 21 Market Street in 1993, becoming a respected member of the community. In 1983, he was interviewed in an edition of the Granada Television current affairs documentary World in Action on how the mentally ill should be treated in the community.

A year after his conviction on charges of murder, the interview was re-broadcast on Tonight with Trevor McDonald.

In March 1998, Linda Reynolds of the Brooke Surgery in Hyde expressed concerns to John Pollard, the coroner for the South Manchester District, about the high death rate among Shipman’s patients. In particular, she was concerned about the large number of cremation forms for elderly women that he had needed countersigned.

Police were unable to find sufficient evidence to bring charges and closed the investigation on 17 April. The Shipman Inquiry later blamed Greater Manchester Police for assigning inexperienced officers to the case. After the investigation was closed, Shipman killed three more people. A few months later, in August, taxi driver John Shaw told the police that he suspected Shipman of murdering 21 patients. Shaw became suspicious as many of the elderly customers he took to the hospital, who seemed to be in good health, died in Shipman’s care.

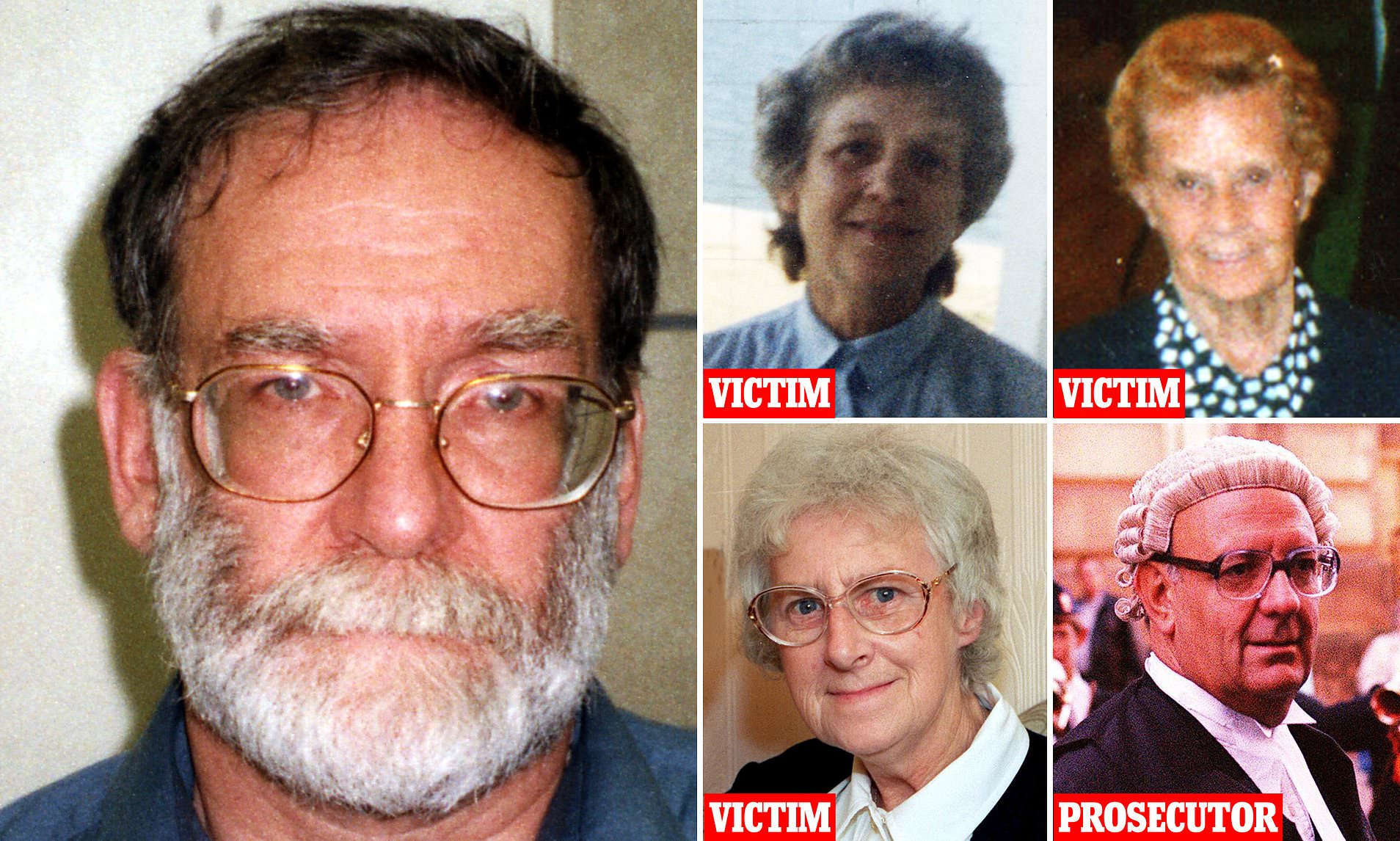

Shipman’s last victim was Kathleen Grundy, a former mayor of Hyde who was found dead at her home on 24 June 1998. He was the last person to see her alive; he later signed her death certificate, recording the cause of death as old age. Grundy’s daughter, solicitor Angela Woodruff, became concerned when fellow solicitor Brian Burgess informed her that a will had been made, apparently by her mother, with doubts about its authenticity.

The will excluded Woodruff and her children, but left £386,000 to Shipman. At Burgess’ urging, Woodruff went to the police, who began an investigation. Grundy’s body was exhumed and found to contain traces of diamorphine (heroin), often used for pain control in terminal cancer patients. Shipman claimed that Grundy had been an addict and showed them comments he had written to that effect in his computerised medical journal; however, police examination of his computer showed that the entries were written after her death.

Shipman was arrested on 7 September 1998, and was found to own a Brother typewriter of the type used to make the forged will. Prescription for Murder, a 2000 book by journalists Brian Whittle and Jean Ritchie, suggested that Shipman forged the will either because he wanted to be caught, because his life was out of control, or because he planned to retire at 55 and leave the UK.

The police investigated other deaths Shipman had certified and investigated fifteen specimen cases. They discovered a pattern of his administering lethal doses of diamorphine, signing patients’ death certificates, and then falsifying medical records to indicate that they had been in poor health.

In 2003, David Spiegelhalter et al. suggested that “statistical monitoring could have led to an alarm being raised at the end of 1996, when there were 67 excess deaths in females aged over 65 years, compared with 119 by 1998.”

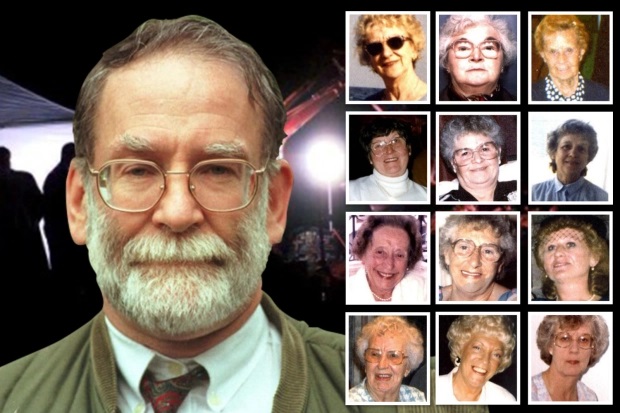

Shipman’s trial began at Preston Crown Court on 5 October 1999. He was charged with the murders of 15 women by lethal injections of diamorphine, all between 1995 and 1998:

Shipman’s trial began at Preston Crown Court on 5 October 1999. He was charged with the murders of 15 women by lethal injections of diamorphine, all between 1995 and 1998:

Marie West,Irene Turner,Lizzie Adams,Jean Lilley

Ivy Lomas,Muriel Grimshaw,Marie Quinn,Kathleen Wagstaff

Bianka Pomfret,Norah Nuttall,Pamela Hillier,Maureen Ward

Winifred Mellor,Joan Melia,Kathleen Grundy.

Shipman’s legal representatives tried unsuccessfully to have the Grundy case tried separately from the others, as a motive was shown by the alleged forgery of Grundy’s will.

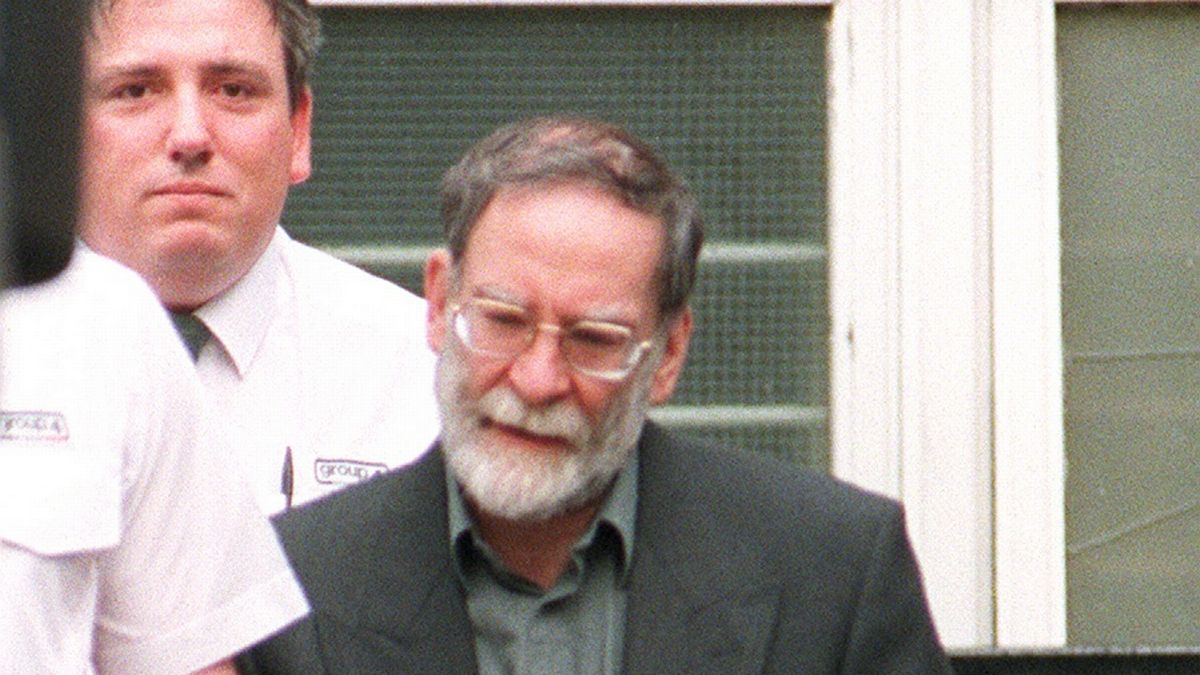

On 31 January 2000, after six days of deliberation, the jury found Shipman guilty of 15 counts of murder and one count of forgery. Mr Justice Forbes subsequently sentenced Shipman to life imprisonment on all 15 counts of murder, with a recommendation that he be subject to a whole life tariff, to be served concurrently with a sentence of four years for forging Grundy’s will

On 11 February, 11 days after his conviction, Shipman was struck off the medical register by the General Medical Council (GMC). Two years later, Home Secretary David Blunkett confirmed the judge’s whole life tariff, just months before British government ministers lost their power to set minimum terms for prisoners

While authorities could have brought many additional charges, they concluded that a fair hearing would be impossible in view of the enormous publicity surrounding the original trial. Furthermore, the 15 life sentences already imposed rendered further litigation unnecessary. Shipman became friends with fellow serial killer Peter Moore while in prison.

Shipman denied his guilt, disputing the scientific evidence against him. He never made any public statements about his actions. Shipman’s wife, Primrose, maintained that he was not guilty, even after his conviction.

Shipman is the only doctor in the history of British medicine found guilty of murdering his patients.

John Bodkin Adams was charged in 1957 with murdering a single patient, amid rumours he had killed dozens more over a 10-year period and “possibly provided the role model for Shipman”; however, he was acquitted and no further charges were pursued. Historian Pamela Cullen has argued that because of Adams’ acquittal, there was no impetus to examine asserted flaws in the British legal system until the Shipman case

Shipman hanged himself in his cell at HM Prison Wakefield at 6:20 a.m. on 13 January 2004, aged 57. He was pronounced dead at 8:10 a.m. A statement from Her Majesty’s Prison Service indicated that he had hanged himself from the window bars of his cell using his bed sheets. After Shipman’s death, his body was taken to the mortuary at the Medico Legal Centre in Sheffield by undertaker’s van for a post-mortem examination. West Yorkshire Coroner David Hinchliff eventually released the body to his family after an inquest was opened and adjourned shortly after.

Some of the victims’ families said they felt “cheated”, as Shipman’s suicide meant they would never have the satisfaction of a confession, nor answers as to why he committed his crimes. Home Secretary David Blunkett admitted that celebration was tempting: “You wake up and you receive a call telling you Shipman has topped himself and you think, is it too early to open a bottle? And then you discover that everybody’s very upset that he’s done it.”

Shipman’s death divided national newspapers, with the Daily Mirror branding him a “cold coward” and condemning the Prison Service for allowing his suicide to happen. However, The Sun ran a celebratory front-page headline; “Ship Ship hooray!”

The Independent called for the inquiry into Shipman’s suicide to look more widely at the state of UK prisons as well as the welfare of inmates. In The Guardian, an article by General Sir David Ramsbotham, who had formerly served as Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Prisons, suggested that whole life sentencing be replaced by indefinite sentencing, for this would at least give prisoners the hope of eventual release and reduce the risk of their ending their own lives by suicide, as well as making their management easier for prison officials.

Shipman’s motive for suicide was never established, though he reportedly told his probation officer that he was considering suicide to assure his wife’s financial security after he was stripped of his National Health Service pension.

Primrose Shipman received a full NHS pension; she would not have been entitled to it if Shipman had lived past the age of sixty. Additionally, there was evidence that Primrose, who had consistently protested Shipman’s innocence despite the overwhelming evidence, had begun to suspect his guilt.

Shipman refused to take part in courses which would have encouraged acknowledgement of his crimes, leading to a temporary removal of privileges, including the opportunity to telephone his wife.During this period, according to Shipman’s cellmate, he received a letter from Primrose exhorting him to, “Tell me everything, no matter what.

“A 2005 inquiry found that Shipman’s suicide “could not have been predicted or prevented,”but that procedures should nonetheless be re-examined

After Shipman’s body was released to his family, it remained in Sheffield for more than a year despite multiple false reports about his funeral.

His widow was advised by police against burying her husband in case the grave was attacked. Shipman was eventually cremated on 19 March 2005 at Hutcliffe Wood Crematorium. The cremation took place outside normal working hours to maintain secrecy and was attended only by Primrose and the couple’s four children.

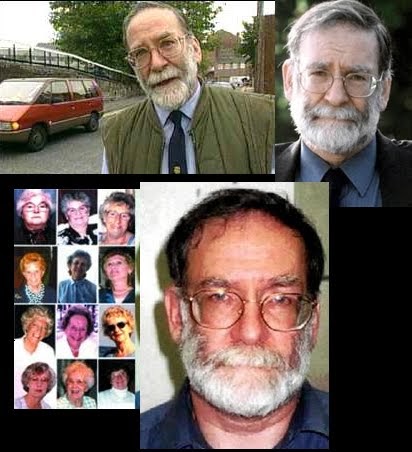

In January 2001, Chris Gregg, a senior West Yorkshire Police detective, was selected to lead an investigation into 22 of the West Yorkshire deaths. Following this, The Shipman Inquiry, submitted in July 2002, concluded that he had killed at least 218 of his patients between 1975 and 1998, during which time he practised in Todmorden (1974–1975) and Hyde (1977–1998). Dame Janet Smith, the judge who submitted the report, admitted that many more deaths of a suspicious nature could not be definitively ascribed to Shipman. Most of his victims were elderly women in good health.

In her sixth and final report, issued on 24 January 2005, Smith reported that she believed that Shipman had killed three patients, and she had serious suspicions about four further deaths, including that of a four-year-old girl, during the early stage of his medical career at Pontefract General Infirmary. In total, 459 people died while under his care between 1971 and 1998, but it is uncertain how many of those were murder victims, as he was often the only doctor to certify a death.

Smith’s estimate of Shipman’s total victim count over that 27-year period was 250.

The GMC charged six doctors, who signed cremation forms for Shipman’s victims, with misconduct, claiming they should have noticed the pattern between Shipman’s home visits and his patients’ deaths. All these doctors were found not guilty. In October 2005, a similar hearing was held against two doctors who worked at Tameside General Hospital in 1994, who failed to detect that Shipman had deliberately administered a “grossly excessive” dose of morphine.The Shipman Inquiry recommended changes to the structure of the GMC.

In 2005, it came to light that Shipman may have stolen jewellery from his victims. In 1998, police had seized over £10,000 worth of jewellery they found in his garage. In March 2005, when Primrose asked for its return, police wrote to the families of Shipman’s victims asking them to identify the jewellery.Unidentified items were handed to the Assets Recovery Agency in May. The investigation ended in August. Authorities returned 66 pieces to Primrose and auctioned 33 pieces that she confirmed were not hers. Proceeds of the auction went to Tameside Victim Support.The only piece returned to a murdered patient’s family was a platinum diamond ring, for which the family provided a photograph as proof of ownership.

A memorial garden to Shipman’s victims, called the Garden of Tranquillity, opened in Hyde Park, Hyde, on 30 July 2005. As of early 2009, families of over 200 of the victims of Shipman were still seeking compensation for the loss of their relatives. In September 2009, letters Shipman wrote in prison to friends were to be sold at auction, but following complaints from victims’ relatives and the media, the sale was withdrawn.

” Trust me i´m a doctor!”/Twitter.

The Shipman case, and a series of recommendations in the Shipman Inquiry report, led to changes to standard medical procedures in the UK (now referred to as the “Shipman effect”).

Many doctors reported changes in their dispensing practices, and a reluctance to risk over-prescribing pain medication may have led to under-prescribing.

Death certification practices were altered as well. Perhaps the largest change was the movement from single-doctor general practices to multiple-doctor general practices.[citation needed] This was not a direct recommendation, but rather because the report stated that there was not enough safeguarding and monitoring of doctors’ decisions.(citation needed)

The forms needed for a cremation in England and Wales have had their questions altered as a direct result of the Shipman case. For example, the person(s) organising the funeral must answer, “Do you know or suspect that the death of the person who has died was violent or unnatural? Do you consider that there should be any further examination of the remains of the person who has died?”

Harold Shipman revealed his guilt as Britain’s most notorious serial killer in just nine seconds, experts have revealed.

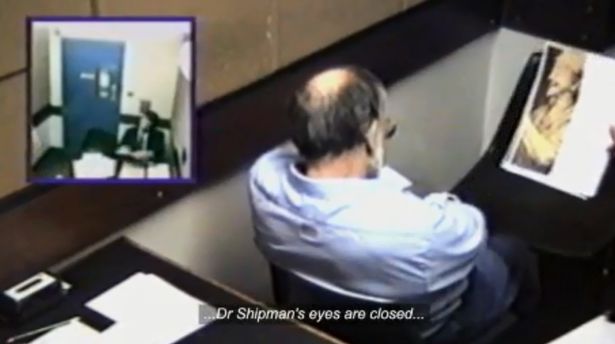

A new documentary has pinpointed the exact moment Shipman outed himself as a mass murderer simply by holding his breath.

Until then the callous GP had refused to open his eyes or even look at police as they quizzed him on the murders of hundreds of pensioners.

According to body language experts from Faking It: Tears of a Crime Investigation Discovery, Shipman made a very simple error during his interview that had huge implications.

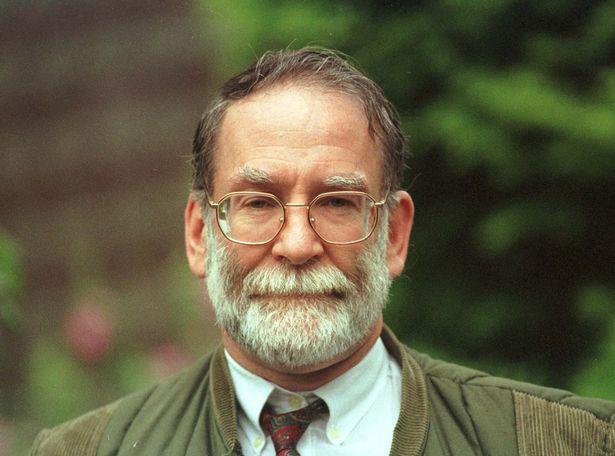

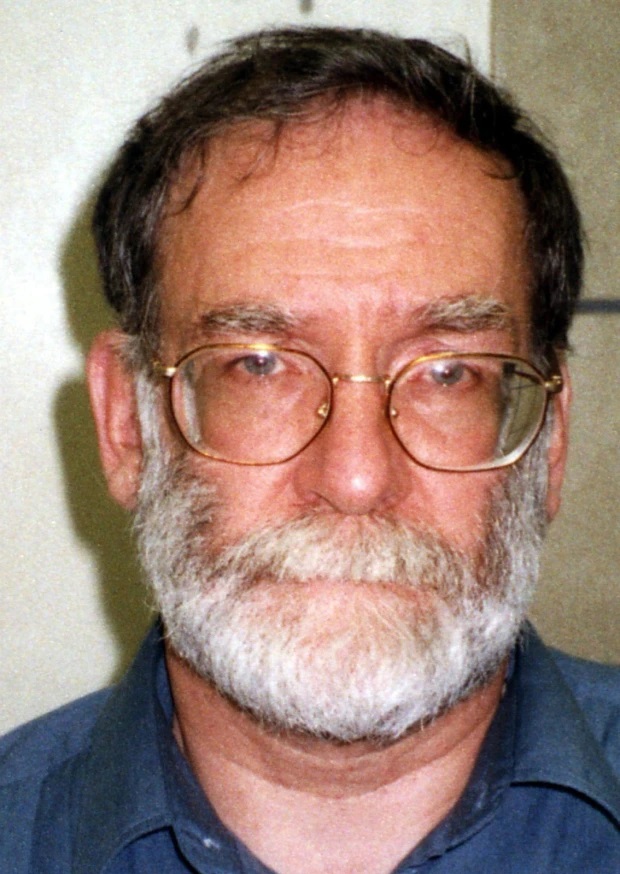

Body language experts have pinpointed the exact moment Harold Shipman revealed his guilt (Image: INVESTIGATION DISCOVERY)

He was uncovered as Britain’s most notorious serial killer (Image: PA)

Shipman became known as ‘Dr Death’

“The name is a problem for him,”

says bodylanguage expert Cliff Lansley who analysed the police tapes.

Elsewhere in the documentary, Cliff tells how Shipman believed he was ‘God like’ and would stay and watch over his victims until the very end.

Shipman is known as Britain’s most notorious serial killer

Shipman was arrested in 1998 and found guilty in 2000 of 15 counts of murder – earning him the reputation of Britain’s most notorious serial killer.

An inquiry later identified a total of 218 victims and estimated his total victim count at 250, about 80% of whom were elderly women.

He was sentenced to life imprisonment, with no chance of release.

But committed suicide at Wakefield prison in 2004, one day before his 58th birthday.

Shipman committed suicide in prison days before his birthday

In 1974, Shipman began working as a GP but just a year later he faced being struck off by the General Medical Council after forging prescriptions of pethidine for his own use. Former detective George McKeating also claimed that ‘Dr Death’ ” injected heroin into his penis ” to get high.

However Shipman was simply fined £600 and had to attend a drug rehabilitation clinic in York.

He then worked as a GP in a number of surgeries in Hyde and became well respected in the community. However during this time he secretly murdered hundreds of patients.

Police eventually became suspicious after finding a forged will leaving him £386,000 of patient Kathleen Grundy’s estate.

After being jailed in 2000, he killed himself four years later.

It was reported by the Sun on Sunday that he had timed his suicide so that he would guarantee Primrose would receive a £100,000 lump sum and further £10,000 a year payments through his GP pension.

HOW is it possible for one man to kill hundreds of people, in plain sight, without anybody noticing?

When the story broke in 1998, Shipman was a popular and respected GP in an ordinary market town called Hyde. At the time, I was living about seven miles down the road in Manchester.

I remember that at first it seemed like a curious local news piece. But it soon snowballed into the biggest serial-killer case in British history.

Shipman was eventually convicted, in January 2000, of killing 15 of his patients.

That was enough to put him away for the rest of his life and he died by suicide in Wakefield Prison in 2004, a day before his 58th birthday.

Twenty years after Britain’s worst serial killer, Dr Harold Shipman, was jailed, that is the question I set out to answer.

But police had investigated more than 100 suspicious deaths and the true extent of his crimes would only emerge after his trial.

The public inquiry in the aftermath of his conviction concluded he had begun murdering his patients as a newly qualified junior doctor in Pontefract, West Yorks, in the early 1970s. He had continued to kill while working as a GP in Todmorden, also in West Yorks, before crossing the Pennines to Hyde, where he commit-ted the vast majority of his murders, between 1977 and 1998.

It is impossible to be certain about the exact number, but the inquiry concluded that, in total, he had killed around 280 people.

Each had died from a lethal dose of opiate, usually diamorphine — pure, medical-grade heroin.

Most had been found in their own homes, often in the afternoon, fully clothed, sitting in front of the fire or a switched-on television.

Exhumation at Hyde cemetery of victim Bianka Pomfret as part of the Shipman enquiryCredit: Manchester Evening News

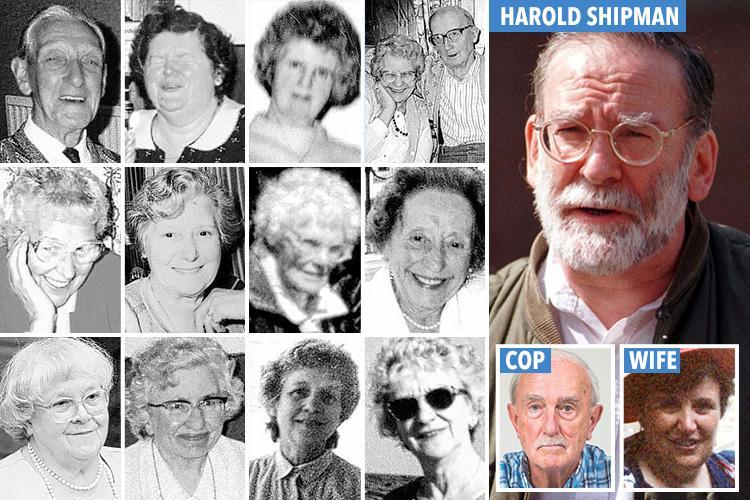

Victims…top row, from left, Norah Nuttall, 65, Jean Lilley, 58, Marie West, 81, Irene Turner, 67, Lizzie Adams, 77, and Winifred Mellor, 73. Bottom row: Kathleen Grundy, 81, Joan Melia, 73, Bianka Pomfret, 49, Maureen Ward, 57, Kathleen Wagstaff, 81, and Pamela Hillier, 68Credit: PA:Press Association

The sign at Shipman’s doctor’s surgery in Hyde,CheshireCredit:News Group Newspapers Ltd

The scale was jaw-dropping and the story has haunted me ever since.

When I was growing up, my mum was seriously ill and our GP was nothing short of a saint.

He had visited her at home regularly and even helped my dad to organise the funeral after she died.

He was the perfect doctor, always prepared to go the extra mile to ensure his patients’ wellbeing. That is exactly how the families of Harold Shipman’s patients described their GP – until they learned he had been murdering their relatives.

Coverage of Shipman’s story has been dominated by two aspects of the case – the scale of his crimes and his motive: How many had he actually killed and why did he do it?

But I wanted to ask a different set of questions, focusing not on the killer but on his victims.

I wanted to know more about who they were and, in particular, to explore whether their age might have been the real reason he was able to evade detection for so long.

The average age of Shipman’s victims in Hyde was 76. More than 200 of them were over 70. Why had he chosen to target such a specific group of patients? Put simply, I wanted to know if our preconceptions and prejudices about the elderly might have enabled Shipman to murder more people than anyone else in British history.

I was fortunate to talk to a huge range of people, all of whom were personally or professionally involved in the case.

Using their first-hand accounts, I was able to build an understanding of the story that completely overturned my preconceptions.

I had always thought of Shipman as a murderer driven by some kind of urge to kill old people. I had pictured his victims as decrepit, housebound old ladies.

But as I talked with many of the victims’ families and friends, I discovered those assumptions could not be further from the truth. While it is true that most of Shipman’s victims were elderly, the vast majority were fit and active members of their local communities, whose deaths were entirely unexpected.

I was shocked to find that when Shipman began killing, during his time as a hospital doctor in the early 1970s, at least two of his earliest victims were young children.

This revelation confounded the idea that he was driven by an urge to kill old people. Shipman was simply a killer.

Shipman pictured with his wife Primrose at a wedding in 1990Credit: Collect

Shipman is believed to be the most prolific serial killer in modern history

The scene at Hyde cemetery in Manchester after police exhumed the bodies of victimsCredit: Men Syndication

But, remarkably, the General Medical Council allowed him to continue to practise – even dismissing the need for a formal disciplinary hearing.

If they had spoken to any of the patients involved, they might have discovered that Shipman was not just using pethidine to feed his own habit. He was also using it to kill some of his patients by administering an overdose.

Shipman continued killing in Hyde in such great numbers that it was almost as if he was trying to wipe out an entire generation of the town. Several months before he was caught, another GP raised concerns about the number of elderly patients who had been dying while under Shipman’s care.

Yet despite clear evidence, the police, coroner’s office and local health authority all failed to investigate properly. These mistakes and missed opportunities are shocking.

But I think the reason why so many authorities and individuals failed to see what seems to have been right under their noses is that they shared a kind of blind spot — one that prevented them from treating the deaths of Shipman’s elderly patients seriously enough.

As I began to think about this, I started to look at attitudes towards old age and the elderly, and the history of geriatric care before and during Shipman’s medical career.

I learned how a fear of hospitals was common among elderly patients; how the idea of dying quietly at home, under the supervision of a caring family doctor, was considered a “millionaire’s death”; and how the cost of looking after an ageing population fuelled an increasingly negative attitude towards old people.

It was against this backdrop that Shipman began murdering his elderly patients in their own homes, where their relatives were more likely to thank the doctor for giving their loved ones a “good death” than question the circumstances.

Shipman’s final victim was Kathleen Grundy, who died on June 24, 1998. She was a former mayoress of Hyde and was well-loved in the town, where she worked for numerous charities and good causes.

Her son-in-law, Phil, told me how she would return from hikes in the Peak District with her grandsons and ask: “Is there any ironing needs doing?”

The night before Shipman killed her, she had been round at a friend’s house watching the World Cup on TV.

Kathleen was a fit and active 81- year-old, with no serious health issues, and her death was entirely unexpected. Yet nobody questioned the circumstances of her demise — which Shipman certified as due to “old age”, as if that in itself was a deadly disease.

When the Covid crisis struck Britain this year, I remember hearing people commenting on how it was OK because it was a disease that “only killed old people”.

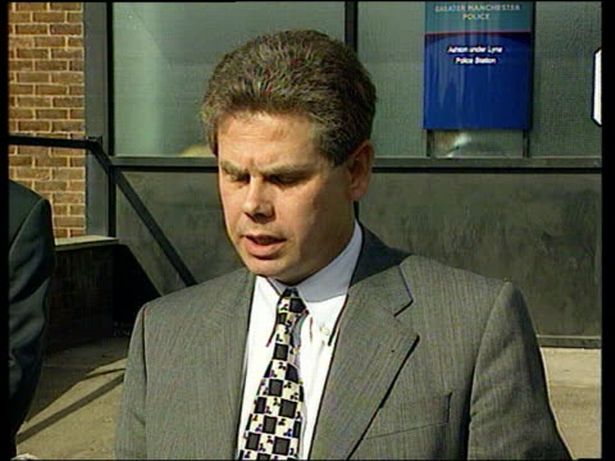

A detective believes Harold Shipman, who killed at least 250 of his patients over 23 years, was able to kill three more people in the time it took for police to take action against him

Doctor Death Harold Shipman was able to kill three more patients because of police blunders, according to the detective who snared him.

Botched early investigations allowed Britain’s most prolific serial killer to continue his murder spree even after detectives probed a spate of deaths, says senior detective Bernard Postles.

Police insisted there was “no case to answer” in March 1998 after investigating the deaths of 21 of Shipman’s patients.

But Mr Postles claims that when he later looked into the case, he was stunned to discover basic checks hadn’t been done.He said: “When I got going with the main investigation I asked for the paperwork in relation to it. I wanted to see what the paperwork said. And there wasn’t any. It’s true to say that investigation had not been thorough and needed to be conducted again.

The time it took for police to take action against the doctor allowed him to kill three more patients

“So I went back to those deaths as well to have a look at them.”

Mr Postles says he soon spotted details that suggested the deaths were suspicious.

Speaking on a new crime series for the BBC, he added: “As we started to investigate them it was apparent that things weren’t right.

“There were a lot of occasions where Dr Shipman had been present or just left the house where somebody was found ,they found in unusual circumstances ,they hadn´t been suffering from long -term illnesses, they were found in the middle of the day, they werefully dressed.“They were really strange. As a consequence of that we started looking at them in more detail.”

Mr Postles says that in the time it took for Greater Manchester Police to take action and find enough evidence to charge Shipman, he killed three more of his patients.

Mr Postles and his colleagues were stunned when they realised the GP had abused his trusted position to commit murder in plain sight.

Detective Bernard Postles believes mistakes by the police allowed the murderer to kill three more patients (Image: Channel 4 News)

He said: “We sat in the office challenging each other on what the alternative explanation was and we couldn’t come up with one because we had a lot of evidence that Harold Shipman had murdered his patients. It was overwhelming in many cases.

”Within weeks of Shipman being charged for murder it became clear there were many more victims.”

Mr Postles said: “It escalated quickly because the public started to ring in because they were recognising similar stories with one of their relatives.

Shipman killed at least 250 of his patients over 23 years

“Within the matter of a couple of weeks we were investigating 60-plus deaths and that continued to escalate. So it was only a few weeks later that we were on over 100 deaths that we were investigating and that was a mammoth task.”

Shipman was jailed in January 2000 and sentenced to life imprisonment. Four years later he committed suicide by hanging himself in his cell.

A public inquiry found that he killed at least 250 of his patients over 23 years.